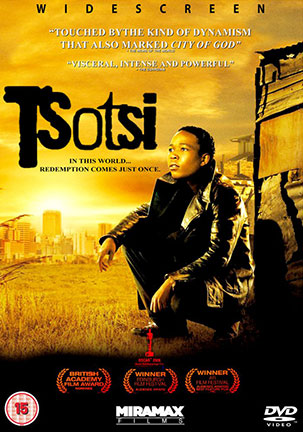

2006 South African film, TSOTSI (THUG)

This was one of several websites promoting the great 2006 South African film, TSOTSI (THUG). Content is from the site's 2006 archived pages and other outside sources. The current official website for the film is found at: http://tsotsi.com/

Rating: R (for language and some strong violent content)

Genre: Art House & International, Drama

Directed By: Gavin Hood

Written By: Gavin Hood

In Theaters: Feb 24, 2006 Wide

On DVD: Jul 18, 2006

Box Office: $2,753,840.00

Runtime: 91 minutes

Studio: Miramax

AWARDS

ACADEMY AWARDS 2006

Best Foreign Language Film of the Year

BAFTA 2006 NOMINATION

The Carl Foreman Award

Film Not In The English Language.

PAN AFRICAN FILM AND ARTS FESTIVAL 2006 AWARD

Jury Prize for Best Feature

SANTA BARBARA FILM FESTIVAL 2006 AWARD

Audience Award

THESSALONIKI FILM FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

Independence Day section, Greek Parliament's Human Values Award

DENVER INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

Audience Award

CAPE TOWN WORLD CINEMA FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

Critics Jury Award

ST. LOUIS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

Audience Choice Award

LOS ANGELES AFI FILM FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

Audience Award

THE TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

People's Choice Award

THE EDINBURGH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2005 AWARD

The Michael Powell Award For Best New British Feature Film

Standard Life Audience Award

© 2017 TSOTSI CREDITS EMBED AND SHARE POWERED

REVIEWS

JHB LIVE

JHB LIVE

JAN 28, 2004

Tsotsi, by Refiloe Mpakanyane

Bit 'bout: Tsotsi is a great South African film which tracks the growth of a hardened, young thief whose childhood has left him alienated from his emotions and his own humanity. The intrusion of a baby into his life brings Tsotsi's defences down as he unwillingly becomes the father he never had and the responsible adult that he never had the chance to become. Presley Chweneyagae is amazing as the troubled thief, who begins his journey unmoved by murders and shootings, yet slowly succumbs to a baby's vulnerability. This is not a cheesy, Raising Helen effort, the movie is gritty and township in every way, from the well written dialogue to the familiar portrayal of a township/ shanty scene.

Highlight: The entire movie rocks! The cinematography is mind blowing, I have never seen isiganga(the open veld) look so beautiful and mystical all at once. This crew of mostly unknown actors is phenomenal and a pleasure to watch.

Lowlight: Not a substantial one to be found yet, perhaps the soundtrack would have been better by including artists other than"Zola"?

IO FILM

JAN 28, 2004

by Gator MacReady

If you crossed Three Men And A Baby with City Of God the result would be something like Tsotsi (an old Afrikaans word for Chav). Yeah, it's a weird combination, but the film is so ruthlessly effective that it will surely draw you in, no matter how unlikely the premise may be.

David is a young man living in the dregs of society in a shantytown outside Johannesburg. His life has been tough and his childhood, in which he lost his mother to AIDS and pet dog to an evil dad, has been brutal. Since a young age he's lived in absolute hopelessness, but clawed his way up to a level of independence, thanks to crime.

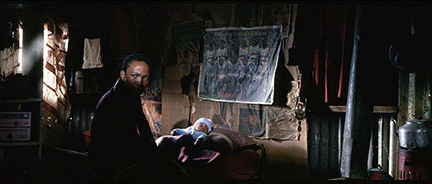

During a carjacking, he shoots a woman outside her home and flees, only to crash a short while later. The reason? He was distracted by the woman's baby in the back seat. Not having the slightest clue what to do next, he tries to look after the child, only for painful memories of his past to come flooding back. He imposes himself on a reluctant local young mother for help and comes to regret his life of crime. After much inner reflection, he decides to give the child back.

It doesn't sound like much, but there's a lot going unsaid in Tsotsi. You can see it in David's eyes and the atmosphere between certain characters feels tense and genuine, something you don't come across every day in a movie. Plus the musical score is deeply emotional and really does creep up on you. It's been rattling around in my head all day.

The acting by a cast of mostly unknowns is perfect. When you think of all the money spent on hollow "talent" in mainstream movies these days, it makes you sad to think that there are so many terrific actors out there so ignored. But how many overpaid stars get to make movies like this?

The cinematography is pretty damn brilliant, too. It's always something I look out for and too often blandness is what I get. Here colours and shadows are used to bring out a unique looking world of deprivation, tinted with atmosphere.

It's not a pretty story of a wonderful life, but Tsotsi is highly recommended. If you leave unaffected, or not even the slightest bit teary, then you have no heart.

THE Z REVIEW

JAN 28, 2004

Adam Whyte

'Tsotsi' means 'thug' in South African slang, and the word has gone on to generate a sub-dialect: tsotsi-taal, the language of the characters in this movie. It is also the nickname of the central character. His closest friends don't know what his real name is. Together, they mug people in the local city. Sometimes mugging stretches to murder. They do what they consider necessary.

After one of the muggings ends up with the victim dead, the group has a falling out, and Tsotsi ends up stealing a car from a woman in her driveway. He shoots the woman when she resists. He drives off with the car. Then he hears a baby crying in the back seat. He finds himself, after being responsible for two murders in one day, unable to leave the baby behind, and ends up looking after it.

At this point, the movie could have descended into a mindless farce, but "Tsotsi" keeps its integrity, and becomes genuinely moving. There are the inevitable scenes of comedy (nappy changing, etc.), but there are also scenes of violence and desperation in the poor village Tsotsi and his friends live in, as well as a horrific moment when Tsotsi comes home to find the baby covered in a swarm of ants.

A subtle relationship develops between Tsotsi and a local mother, to whom Tsotsi takes the baby to have him fed. Tsotsi is in such an isolated world of violence that the first time he goes to her, he threatens her at gunpoint to have the baby fed. It wouldn't occur to him to ask politely.

The baby could have fallen into the laps of any of these criminals, because the movie is ultimately saying that though these thugs seem heartless, they have good sides that they have forgotten, or hidden for their own protection. There are flashbacks of Tsotsi's childhood, and the message of the movie becomes: if South Africa (and the world) doesn't want thugs like these guys, it shouldn't allow them to have the childhoods they have. One of the movie's most haunting images is the sight of a pile of large construction pipes, each one with children sleeping in them to get out the rain.

"Tsotsi," directed by Gavin Hood, tells a story that Hollywood could have easily done, but unlike the hypothetical American version, this one does not clean the grime out of the characters' lives. It doesn't excuse them their crimes, but it slowly evolves into a social commentary about the class distinctions and social problem in post-apartheid South Africa.

That alone though is not even for a movie to work; a human face needs to be attached, and Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) is a superb character. He isn't some sort of likeable crook. He's a wounded, violent young man who discovers a little about himself when he finds the baby: a little about who he is, and what he does, and what he has hidden from himself, and why.

SCREEN INTERNATIONAL

AUG 22, 2005

by Allan Hunter in Edinburgh

22 August 2005

Touched by the kind of dynamism that also marked City Of God, Tsotsi brings a fresh energy to familiar themes of crime and redemption. Based on a novel by Athol Fugard, it offers an unflinching portrait of post-apartheid South Africa; the lawless shanty towns and lives bereft of hope. It also manages to look beyond the despair to tell an arresting human story of one young man's journey towards the possibility of change.

Critical support should help position this as an essential festival item with real commercial potential in the hands of a committed distributor: it enjoys a North American premiere at Toronto after screening at Edinburgh at the weekend.

The third feature from writer-director Gavin Hood feels as fresh as new paint in its determination to reflect the realities of shanty town communities rife with casual crime and lethal violence. There is a sense here of a South Africa that has become as wild as the old west. Contemporary reportage is allied to classical storytelling with a central figure who could have strayed straight from the mean streets of a punchy, post-War film noir. It is easy to imagine Sam Fuller in the director's chair or Richard Widmark as the hoodlum finally able to embrace his better instincts.

Neither his feature debut A Reasonable Man (1999) nor In Desert And Wilderness (2001) established Gavin Hood as an international name but Tsotsi should remedy that; crisply edited, compact and compelling, it is filled with bravura moments.

"Tsotsi" means thug and it is also the nickname that has been applied to David (Chweneyagae). Orphaned by AIDS, he has been forced to raise himself, honing his survival instincts and growing indifferent to the hurt he causes, the anger he carries or the lives he damages. The aftermath of one crime finds him beating one of his friends to the point of death.

Later, he steals a car and when the owner refuses to relinquish the vehicle he shoots her. It is only after driving away that he realises there is a young baby in the back seat. He doesn't kill the child or abandon it. Instead, he bundles it up in a brown carrier bag and takes it home. Having the responsibility for another human reawakens his long dormant compassion for others and leads to the realisation that he cannot continue to live his life like this.

Tsotsi's success lies in the way that it manages to change our perspective on the central protagonist. At first, David seems like the worst nightmare of a law-abiding citizen. Wide-eyed and ruthless, charismatic actor Presley Chweneyegae seems to seethe with contempt for the world. He is a walking powderkeg who sees no reason to abide by society's rules because it has done nothing for him.

When he starts to acknowledge the humanity of others, we connect to the struggle within him until the film's finale becomes emotional, edge of the seat high drama.

Filmed entirely on location, Hood avoids the obvious approach of gritty, guerrilla-style film-making to create a film with a polished cinematic sweep and a sense of eerie beauty lurking in the most unexpected places.

VARIETY

AUG 23, 2003

by Leslie Felperin, 23rd August 2005

Rapturously received by premiere auds and sparking acquisition interest from mini-major studios at the Edinburgh film fest, intense Blighty-South African co-prod "Tsotsi" has the right stuff to be a breakout hit if distribs market it cannily. The third film by helmer Gavin Hood ("A Reasonable Man"), contempo-set "Tsotsi" tells of a township hoodlum (an ace debut for Presley Chweneyagae), who learns to care for an infant whose mother he shot. Powered by a pounding soundtrack of dance hall Kwaito music, the pic has vital, urban energy similar to the Brazilian crossover "City Of God" and but with a tauter, more conventional storyline.

The plot has been carved by writer-director Hood from a sprawling novel by Athol Fugard ("Boesman And Lena") and transposed gracefully from the early '60s to the present. More than most recently exported South African-set pics, "Tsotsi" gets across the ruthless violence in cities like Johannesburg, the setting here.

Authenticity is enhanced by location use, while the main characters speak Tsotsi-Taal, a patois made up of English, Africaans and words from several tribal dialects that requires subtitles throughout.

The title character Tsotsi's name means literally "thug," a moniker he picked up on the streets after running away from a brutal father (Israel Makoe) and a mother (Sindi Shambule) dying of AIDS. (Young Tsotsi is played in flashbacks by Benny Moshe, the grown Tsotsi by semi-pro legit thesp Chweneyagae.)

The eventual revelation of Tsotsi's real name is cleverly used to signal his recovery of human values.

Tsotsi and his gang stab a man on the subway with an ice pick to steal his wallet in a tense, wordless scene that makes fine use of sound and close-ups. Afterward, at a township drinking den, Tsotsi brutally beats fellow gangster Boston (Mothusi Magano) when the latter dares to ask if there was ever anyone Tsotsi really cared about.

Seemingly on a whim, Tsotsi hijacks the car of a middle-class black woman (Nambitha Mpumlwana). He casually shoots her and drives off, only to discover her baby boy in the back seat. Abandoning the car, he reluctantly takes the nipper home in a paper shopping bag.

Caring for the child gradually repairs Tsotsi's broken spirit, a trajectory that could have been mawkish or unbelievable in lesser hands, but which Hood and particularly Chweneyagae make utterly convincing. To feed the mewling infant, Tsotsi pressgangs the services of a widowed single mother, Miriam (Terry Pheto, luminous), who shares her milk at first at gunpoint and later voluntarily.

Slightly slower third act sees Tsotsi return to the baby's parents' home with his gang for a burglary, where events take an unexpected turn. Final suspenseful scene ends on transcendent, just-so note.

Overall, pic strikes nice balance between generic, gangster movie set-up and purely localized trappings. Perfs by leads are strong enough to distract from limitations of some supporting players.

Widescreen lensing by Lance Gewer is aces, offering a dense panorama for the drama. Several flashy crane shots capture the teeming township streets, while dramatic quasi-noir lighting that renders the seamy atmosphere of Tsotsi's hovel contrasts with jewel-like tones of Miriam's house.

Editing is generally unobtrusive except in a scene that flash cuts between older and younger incarnations of Tsotsi running across a rain-drenched landscape, a segment that would feel melodramatic if it weren't for the accompanying hard-edged Kwaito soundtrack.

Track could make a strong album appealing to the world-music niche, though it lacks the well-known Western hits that made the accompanying album for "City of God" a minor hit.

HOLLYWOOD REPORTER

AUG 30, 2005

By Ray Bennett, August 30th 2005

LONDON -- "Tsotsi" means "thug" in the patois of South Africa's townships, and it also is the name of the title character in writer-director Gavin Hood's tough-minded film about a young man fighting against his own history of violence.

Brutal but believable, the film in some ways harks back to early Hollywood, when Jimmy Cagney or Richard Widmark played callow villains out of their depth in everyday life. With its highly original setting, "Tsotsi" will appeal to fans of thoughtful crime pictures beyond the festival and art house circuits.

The movie screened in London and was shown at the Edinburgh Film Festival. It also will screen at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Seldom has the desperate poverty of the shantytowns that sprawl beside cities such as Johannesburg been shown so vividly as in Hood's fast-moving story about a fearsome gang leader (Presley Chweneyagae) who unexpectedly discovers a kind of life different from one of violent crime.

Tsotsi leads a gang of vicious petty thieves but is frustrated by their pointless existence, and one day his anger explodes; he turns on one of them and beats him to a pulp. Horrified by his own behavior, Tsotsi flees until he finds himself in a wealthy part of the city.

In pouring rain, he spots a woman pulling up to her garage door. Almost without thinking, he does what comes naturally and steals the car at gunpoint, wounding the woman in the process. Racing away, Tsotsi hears a baby crying in the back seat and totals the car.

The young criminal's reaction when he finds himself taking care of the infant after the crash and the impact it has on his violent life makes for a winning tale. When he encounters a young mother (Terry Pheto) in the ghetto and she responds to his plight, the story becomes both darker and more absorbing.

Hood's filmmaking is accomplished, Lance Gewer's cinematography exceptional and there are fine performances throughout, especially by Chweneyagae as the memorably tortured young Tsotsi

FINANCIAL TIMES

AUG 30, 2005

By David Archibald, August 30th 2005

Gavin Hood is all too aware of the violent epidemic that plagues his native South Africa. "My mother was carjacked twice with a gun in her face," the filmmaker says. "I've been mugged at knife-point, my dad's been mugged at gun-point." Yet in spite of his experience he speaks of hope rather than fear. "Part of your response is anger but I have to believe that people are capable of rising above that behaviour."

This spirit of optimism underpins his powerful third feature, Tsotsi. Based on the only novel by Athol Fugard, the acclaimed South African playwright, Tsotsi deals with violence and brutalisation in post-apartheid South Africa.

Tsotsi means "thug" or "gangster" in Tsotsi-Taal, or gangster talk, the South African township slang. Tsotsi is also the eponymous anti-hero who leads a youthful group of callous gangsters. Their activities are brutal and bloody, terrorising the community from which they emerge. One night Tsotsi carjacks a BMW, shoots the female owner and drives off before he realises there is a three-month-old baby in the back seat. His dilemma is the starting point for a journey of self-discovery that presents the possibility of redemption.

"It's a coming-of-age story about rising above your own anger and rage to become a man," says Hood, the film's writer and director. "That story is timeless and universal. It happens to be set in South Africa but it could be set in 19th century London or present-day Mexico City."

The backdrop to Fugard's novel is the politics of 1950s apartheid. But in this energetic UK/South Africanco-production, Hood has updated the novel to deal with contemporary concerns: Tsotsi is orphaned by Aids. "We've repoliticised the original," he says. "Aids is the elephant in the room. It's a monumental crisis."

Hood should know what he is talking about. He began his film career making educational dramas for the South African Department of Health, spending considerable time in shantytowns just as the HIV/Aids epidemic began to bite. Numbers vary but Statistics South Africa estimates that 4.5m South Africans, more than 10 per cent of the population, have the virus.

But Aids is only the backdrop to the film; it is never mentioned. The real focus is the emotional journey of Tsotsi, skilfully played by 19-year-old newcomer Presley Chweneyagae, who was plucked from the obscurity of community drama to play the lead role.

"The one thing that Fugard's novel is really beautiful at is the inner journey of Tsotsi," says Hood. "So much of a novelist's voice is what the character is thinking, but in film you only have two things at your disposal - what your characters do and what they say. Tsotsi doesn't say very much so you have to focus on what he does. The trick in writing a screenplay is how to write the visual beats from wide shots to close-ups - to generate the inner journey without ever saying a word."

Tsotsi occupies a world of minimal colour - shot on location in Soweto and Johannesburg - reflected in the dark tones of his clothes and of the shack that he inhabits. But this involving film also reveals the complexity of shantytown life. "Some films tend to show the ghetto as only hell," says Hood. "There is a lot of hell, but there's a lot of joy. Life is both brutal and not brutal, but people have this amazing ability to be joyous in adversity. It's terribly patronising of Europeans to think of Africa only as an Oxfam commercial."

The dialogue in Tsotsi is a blend of Afrikaans and local vernacular languages such as Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana and Sotho.

"These kids have invented their own language," says Hood. "It's ghetto language, or gangster language. It's the language of the streets." But he is more concerned with how the language is performed, not just spoken. "I wrote the script in English and then it was translated. But I'm really interested in a universal language of emotion.

"When I storyboard, I look for emotional beats. I don't work with actors on line-readings. I work with actors to get into the right emotional zone and work out where these emotional beats are."

The focus on township life has brought comparisons with the 2002 Brazilian hit movie, City of God. Although similar in subject matter, stylistically the films are very different. While City of God has a rough and ready aesthetic, Tsotsi is polished. "The texture comes from the art direction and the environment," says Hood. "I want you to feel the grit, not because I gritty up the film but because the grit is in there; in the corrugated iron, in the dirt, in the smoke."

City of God also has more of a documentary feel, of the audience observing the action from outside, whereas Tsotsi pulls the audience in. "We kept the camera still," says Hood, "because it's often about subliminal, as opposed to verbal, communication. It's often through the eyes. So we filmed it so that the characters are almost looking at the camera."

Reflecting Hood's optimistic worldview, the film rejects the bleak ending of Fugard's novel by creating a space for redemption. He suggests that it reflects the reality of the times. "In South Africa in the 80s, it felt hopeless. In the current political climate, in spite of epidemics, in spite of poverty, in spite of refugees fleeing war, it does not feel as hopeless as under apartheid. There is still some sense of hope."

It is this sense of hope that helped catapult the film into the hearts of audiences when it received its world premiere last week at the Edinburgh International Film Festival. It is destined for a bigger stage at Toronto in early September, and Hood is delighted with the international response. "At the moment we're pleased that it's getting such a great reception outside South Africa," he says. "The next step is, please God, that somebody buys it."

THE STAR SEP 19, 2005

By Janine Walker, September 19, 2005

If South Africa ever has a realistic chance to win an Oscar for Best Foreign Picture it will be with this harrowing but brilliant picture - one of the finest to come out of this country.

At long last we've moved away from the candid camera gags and farcical fare that seemed for too many years to be the core of the local film industry and proved that even with small budgets this country can make meaningful cinema. It is now up to local audiences to support the industry.

Tsotsi can be compared to Brazil's potent and disturbing City of God. In both the viewer is taken into a world of extreme poverty, degradation, violence and abject immorality. Survival is not of the fittest but of the most brutal.

In Gavin Hood's Tsotsi - based on a novel by Athol Fugard - we move to the mean streets of an almost unrecognisable Jozi as an emotionless and unfeeling gang-leader and his followers terrorise the helpless and innocent.

We may be called the rainbow nation but none of these characters is living the new South African dream. This is a nightmare and there's no waking up from it. The story focuses on the people that society has abandoned and forgotten. The way they extract their revenge during the course of their pointless existence is brutally sickening and horrifying.

And then the central character Tsotsi undergoes a life-changing experience. He hijacks a car only to discover that he has also inadvertently kidnapped a young baby. Slowly he begins to discover his long-lost humanity and compassion.

The film isn't always easy to watch and it will make you uncomfortable but it is emotionally gripping from start to finish.

It works as well as it does thanks to the electrifying performance from newcomer Presley Chweneyagae. He makes you question the very civility that you take for granted. What is remarkable about his performance is that he is able to make the viewer feel compassion for a monster who has only recently discovered his own.

Hood examines issues of redemption but cleverly avoids sentimentality.

In the end it is an even better film than City of God. Does it deserve an Academy Award? Absolutely and that isn't a partisan point of view.

Rating: 9 out of 10

HOLLYWOOD ELSEWHERE SEP 20, 2005

By Jeffrey Wells

Gavin Hood's Tsotsi has become the big stand-out at the end of the Toronto Film Festival.

Gavin Hood's Tsotsi has become the big stand-out at the end of the Toronto Film Festival.

It was first shown on Wednesday night, right opposite the In Her Shoes viewing at Roy Thomson Hall, and by this time many of the top-tier journalists had left town, so there haven't been a lot of insiders hopping up and down about it. And yet today -- Saturday, 9.17 -- it won the Toronto Film Festival People's Choice award.

I also know Tsotsi has aroused the persistent passions of at least one would-be distributor. And that it touched enough people at the recently-wrapped Edinburgh Film Festival to win the Audience Award, along with the Michael Powell award for Best New British Feature.

Even the notoriously hard-nosed critic Len Klady told me early this afternoon, "I hear it's very good."

As I waited to see it Thursday afternoon I thought I might be in for another hyper- cut City of God crime-in-the-slums movie, but it was something quite different.

Set in a rancid Johannesburg shantytown, Tsotsi (pronounced Sawt-see) is about an ice-cold teenage thug (Presley Chweneyagae) who discovers a small spring of compassion in himself when he starts to care for an infant boy who happens to be in the back seat of a car he's stolen.

What is this film doing exactly? It's reminding audiences in a believably non-sappy way there are sparks of kindness in even the worst of us. It's a very Christian- minded movie, in a sense.

It may sound sentimental and manipulative, but it's not. But neither is it sadistic or repellent in some flashy, gun-fetish way. It's real and unblinking, but it also lets you feel what's happening. But not too much...just enough.

Emotions suppressed but leaking out anyway...the emotion you'd rather not feel but which won't leave you the fuck alone...the emotions that you stopped letting in when you were eight or nine but have always been there...conveying these in a film is always a stronger, more poignant thing than having some emotionally healthy actor or actress cry their eyes out or hug everyone to death...please.

I said this in a Wired item posted this morning, and here it is again: unlike Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne's Palme d'Or-winning L'enfant, which it vaguely resembles, Tsotsi has a potential to snag some decent coin as well as Oscar nominations (Best Foreign-Language Film, Best Actor, etc.), critics awards, Golden Globe awards, etc.

How do I know Tsotsi will sell tickets? Because my good and kindly Toronto friend Leora Conway, who know what she knows but isn't tremendously knowledgable or sophisticated about movies, went apeshit after seeing Tsotsi at the Wednesday night premiere...she was beaming when she told me about it afterwards, and said it made her cry at the end.

Bad guys and wailing babies...it's bound to be the very next phase. Tsotsi, L'enfant and Michael Davis's Shoot 'Em Up, the comically violent Don Murphy-New Line movie with Clive Owen as a gun-toting Man of Few Words protecting a baby who's only a day or two old. Any others?

Wait a minute...I see a TV series in this. A wise-cracking yuppie assassin (think John Cusack) whose girlfriend dies just after giving birth..this hard-assed guy has to juggle diapers and nanny-care while taking care of business. And he's got a nosey female neighbor who's secretly hot for him.

I had breakfast early this morning with Hood, Tsotsi's director and writer (the film is based on a novel by South African playwright Athol Fugard), and Presley Chweneyagae, who plays the title role, at the Sutton Place hotel, and we batted it around some.

Hood said he's always been terrified of sentimentality and being mushy in movies, and says that his mantra during shooting was that there's always got to be more going on within a character than what he lets out.

Hood said he wanted to use formal compositions and a slower editing style than the one popularized by City of God because I didn't want to seem like I was saying 'me too'...I didn't want to come in second.

Hood says he feels more of an affinity with the shooting style of director Walter Salles (The Motorcycle Diaries) and particularly Sales' Central Station than he does with City of God director Fernando Meirelles.

The language that Chweneyagae and his costars speak is known as Tsotsi-taal (the first word meaning thug and the second meaning language). It's a mixture of several tongues including English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, Sothu and Tswana.

To qualify for Academy consideration, Tsotsi is opening in South Africa today for one week.

Hood showed the finished film to Fugard, 87, at his San Diego home just before the Toronto Film Festival began. Fugard was delighted and wrote that Tsotsi is everything in my wildest dreams that i hoped it would be...it is far and away the best film that has been made of something I have written [and] it will ranks as one of the best films ever to come out of South Africa.

This is one of those it films. I could feel the rooted energy from the get-go...from Hood's hard-edged direction, the elegant photography and Chweneyagae's mesmerizing performance as an ice-cold psychopath who now and then devolves into a terrified three-year-old. It all coagulates into something steady and whole.

If I know anything about this business, somebody is going to pick this film up fairly soon. But they'll need to move quickly once they do, so hubba-hubba and chop- chop.

AIN'T IT COOL NEWS SEP 24, 2005

October 24th 2005

Hi, everyone. "Moriarty" here with some Rumblings From The Lab...

I heard a few things about this film after it played at Toronto, but I made sure I didn't read anything too detailed. I wanted to see it as fresh as possible. When I saw it show up on the schedule of press screenings for the fest, I made it my top priority out of all the screenings.

So, of course, I showed up late. Or rather, I got to the AFI campus on time, then spent 20 minutes trying to find parking. I eventually did, but all the way down by the front gate. When I finally got to the Goodson, the doors were all locked. It took another five minutes to get inside.

And despite such a frustrating start to the screening, I'm pretty sure this is the best thing I've seen all year.

Written and directed by Gavin Hood, adapted from a novel by Athol Fugard, TSOTSI is a powerful, piercing story about compassion that works on a personal, emotional level but also makes some cogent points about the larger world. It may be one of the most immediately accessible parables I've ever seen. You can watch the film without ever thinking of the larger implications, and you'll still bave a complete experience. On the other hand, if you open yourself to this film's message, it's nothing less than transformative.

Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) lives in a shack in a shantytown on the outskirts of Johannesburg, South Africa. He's 19 years old, already hardened by years on the streets, and he runs with a rough crew. They're all scared of him, though. He's crazier than any of them. It's like there's some essential part of him that has died. Tsotsi isn't even his real name. It's just street slang for "thug" or "gangster," and it's the only name anyone has for him. The only people he shows any regard for are his friends, Boston (Mothusi Magano), Butcher (Zenso Ngqobe), and Aap (Kenneth Nkosi).

One night, after a brutal mugging escalates into a murder, Boston dares to challenge Tsotsi's sense of wrong and right. Boston studied to be a teacher, but got sidetracked by his own alcoholism, and he seems himself as the one member of the crew who knows better. He interrogates Tsotsi, practically taunts him, until Tsotsi snaps and beats the living shit out of Boston, almost killing him.

Tsotsi wanders off into the night, torn up and determined to stay sealed off, to not let anything touch him at all. In a harrowing scene, he confronts a woman in her driveway and, at gunpoint, steals her car, shooting her in the stomach and leaving her for dead. Once he crashes the car, he finds something unexpected in the backseat: an infant boy.

The entire film, from that point on, is all about Tsotsi grappling with the question from Boston that set him off in the first place. "Who do you love? Have you ever loved anything? Your mother? Your father? Even a dog?" Using very smart cuts back to Tsotsi's childhood, we learn not only what drove him onto the streets, but also what moments define him. What baggage does someone carry to make them into a killer? Through it all, Presley Chweyneyagae's performance never strikes a false note. He is nothing less than riveting in every scene.

I'm sure that the intense visceral reaction I had to certain scenes has to do with the fact that I'm a new parent. Tsotsi isn't equipped to deal with the baby he finds, and some of the early mistakes he makes with the baby are horrific. There's one moment involving ants that had me crawling out of my skin. When Tsotsi needs to feed the baby, he targets a young mother he sees carrying her own infant. He forces her to nurse "his" baby at gunpoint. Miriam (Terry Pheto) is terrified, but she can also see that the baby needs help, and her maternal instinct kicks in.

Tsotsi is changed by the experience, but not in the easy, happy Hollywood way we're almost conditioned to expect. He's a confused kid when all is said and done, not Lex fucking Luthor. This isn't some master plan he's following. He reacts based on pure instinct. He's rotten, truly corroded at the start of the film. The movie shows you why, but it doesn't make excuses for him. Even some of the "good" things he does in the film are destructive, awful. That's all he knows. Gavin Hood's shooting style is pretty much the exact opposite of Fernando Mierelles, but this film affected me in much the same way that CITY OF GOD did. Hood's got an amazing eye, using his full 2.35:1 frame to maximum effect. The film is sleek, never frantic. There's no shaky cam here. The last thing you think about during even the tensest moments is the camera. Hood makes you care about these people, creates a true intimacy with them. It's one of those indefinable gifts that marks a great filmmaker... the ability to make you forget you're watching a movie. One of the reasons I railed so hard on DOMINO last week was because that sort of hyper-aware stylization distances me more than it draws me in. You're always aware, "Yes, this is a movie," because the movie keeps reminding you, over and over. With TSOTSI, I just got lost in the everyday reality of life in a Soweto shantytown.

You want an explicit political message? You could say that the wealthy countries of the world are Tsotsi, violent and frightening, seemingly without any boundaries, and the baby represents the third world. Until we learn to care about those who need our help, we are fundamentally selfish, living lives of destruction. The film doesn't wallow in images of poverty, and it doesn't oversell things. It's just that I can't imagine the reality of life for Tsotsi. In one scene, he goes to visit a stack of short concrete pipes where he used to live. He meets the kids who live there now. As young as Tsotsi seems (and 19 seems very young to me these days), seeing those seven and eight year olds, homeless and alone already, it really drives home just how long Tsotsi's been at it. As I understand it, Hood changed several things when adapting this from Athol Fugard's novel. It's a tremendous piece of film writing, managing to tell a story that's largely internal without resorting to voice-over narration. He shows us what's inside Tsotsi. He makes connections clearly without belaboring the point. What's impressive to me is how close we came to seeing a very different version of this film. At one point, Hood was thinking about making the film in English, with internationally recognizable actors. Instead, he opted for unknowns, performing in "Tsotsi-Tall," the common language of the streets of Soweto. Great choice, and it makes all the difference. Using authentic "kwaito" dance music on the soundtrack gives the film a unique flavor. Director of photography Lance Gewer's work is rich and memorable, warm but not overly romantic. He doesn't pretty up this world, but he does manage to find some beauty in it.

I would consider TSOTSI to be an important film for a post-Weinstein Miramax. In a world where the best performances of the year are the ones that are truly recognized, then both Presley Chweyneyagae and Terry Pheto would be nominated for Oscars. You may see other great performances this year, but this is the definition of great film acting. I believe both of them utterly every time they're onscreen. Harvey Weinstein could have turned this film into a buzz event. He could have sold it to the Academy. That was his gift, the reason Miramax was such a reliable Oscar machine. Now the new Miramax faces a test of their own prowess. I pray they rise to the occasion.

TSOTSI is both entertainment and art, and it marks Gavin Hood as one of the most important new voices in film. It plays as part of the AFI Film Festival in Hollywood on Friday Nov. 4th, at 7:15, and again on Saturday the 5th at 3:00. I'll definitely be there for at least one of those two shows, and I can't stress this strongly enough: do not miss it.

"Moriarty" out.

SPIRITUALITY & HEALTH SEP 28, 2005

by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat

We lived in such jaded and cynical times that it has become harder and harder for us to believe in the possibility of somebody totally changing and becoming a new person. Yet in a spiritual world, this happens more than we know. There are so many lives that can be turned around; all it takes is someone to serve as a catalyst for the transformation. This is what happens in Tsotsi, a film set in Johannesburg, South Africa. It is directed by Gavin Hood and based on a novel by Athol Fugard.

To prepare yourself for this extraordinary emotional experience, you must allow yourself be immersed into a cruel and capricious world of random violence and incredible poverty. It is also best to set aside any ideas you have about law and order, sociopaths, and the gap between the haves and the have-nots. Stay with the main character and his descent into darkness, and let yourself feel the loneliness, the anger, and the alienation that he has experienced. Feel also the great harm he brings into the lives of others by his cruel actions. Do not allow your personal ideals about what is good and what is bad to take you away from this story.

Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) is an angry young thief who enjoys gambling with his buddies and stealing from others on the rough streets of Johannesburg. One day he and three members of his gang spot a man with a roll of bills near the subway station. They board the crowded train and surround him. One member of the gang stabs the victim in the heart, and the group flees the scene with the money.

Boston (Mothusi Magano) is repulsed by the senseless violence of the robbery and confronts Tsotsi. He wonders whether he has any "decency" at all. Tsotsi answers with his fists; he beats the conscience-stricken Boston senseless. Tsotsi runs out into the night and hijacks the car of a middle-class African woman (Mothusi Magano). When she tries to stop him, he shoots her. Later he crashes the car after hearing a noise from the back seat and discovering a baby.

Tsotsi puts the infant in a paper bag and takes the child back to his tin hut in shantytown. In flashbacks, we learn of the reason Tsotsi left home: a violent incident which followed his father ordering him out of the room where his mother was dying of AIDS. Tsotsi's father breaks the back of his son's dog with two kicks. Tsotsi flees home and lives in some open-ended drainage pipes outside the city with other orphans and runaways. He learns to look out for himself and to take advantage of the weak and the distracted.

Realizing that he cannot properly feed and take care of the baby, he spots a young woman with a child on her back and follows her home. Miriam (Terry Pheto) turns out to be a widow who makes a meager living sewing and selling mobiles she has created out of shards of glass. Tsotsi forces her at gunpoint to feed the infant. He learns a little about her life, and he is touched by her tenderness with the baby.

In one of the many poignant moments in the story, Tsotsi follows a crippled man in a battered wheelchair into an urban underpass. There he pulls a gun on the man and orders him to hand over the tin can he'd been collecting money in from people in the subway station. Tsotsi learns that the man lost the use of his legs working in the mines, when a beam fell and crushed them. Tsotsi shares the story of losing his beloved dog, and decides not to take the old man's money. Something inside him has already changed. It is the start of a miraculous turnaround in his hard-pressed life.

"Tsotsi" means "thug." The protagonist has adopted it as a shield in a world that seems loveless and wayward at the same time. For those who have eyes to see, the story of the thief on the cross next to Jesus who repents is an indication that grace is operative to anyone, anywhere, and at anytime — even the last possible moment of a life. We don't have the words to describe the experience of watching Tsotsi's slow journey to kindness and human decency after living with the baby. So let us instead share the following quotation by Ellen Bass which says it better than we could:

"There's a part of every living thing that wants to become itself: the tadpole into the frog, the chrysalis into the butterfly, a damaged human being into a whole one. That is spirituality."

AIN'T IT COOL NEWS JAN 23, 2006

Moriarty, January 23th 2006

...

1. TSOTSI

No question about it. Have you seen the trailer yet? Check it out for just a hint of what you can expect at the end of February when Miramax releases the film to theaters. Gavin Hood's made a few films before now, but nothing that I've seen. I'm positively dying to see what he does next. Working from Athol Fugard's only novel, Hood has made the most human, heartfelt, hopeful film of the year, and although I'm not big on the whole "movies can change your life" thing, I think this is the sort of film that genuinely can affect the way you view the world. More than anything else, this has been a year in which I've confronted the idea of personal responsibility, and also the notion of being responsible for others. I'm a selfish person by nature. I think you have to be to some degree to be a writer or a director or to work in any artistic field. You have to be able to shut out the world around you and focus on your inner life. You have to be willing to shut out distractions if you want to finish things. And now, for the first time in my life, there's something or someone who I am more interested in... more invested in... than myself. Having a child changes the rules...or at least it has for me. Realizing that there is someone who depends on you for everything, for every need or want, is humbling, and it's forced me to reprioritize everything.

Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) has spent most of his life living from impulse to impulse, but all that changes when he finds himself responsible for the life of an infant. His performance is absolutely without artifice, and there are moments where it's almost too much to take emotionally. This is a film that never once has to resort to sentiment, because the depth of feeling in it is so profound that it overwhelms you. I love that I didn't recognize anyone in the film as I watched it. I love the authenticity of the world the film is set in. I love the pitch-perfect ending to the movie. This is a film that I will still be watching and discussing and remembering for years to come, and it marks a major debut by someone I hope becomes one of our most prolific new filmmakers.

ROTTEN TOMATOES

JAN 28, 2014

Tomatometer Score: CRITICS 82% | AUDIENCE 86%

RELEVANT MAGAZINE FEB 18, 2006

By Maryan Koopman, 18th February 2006

Foreign films are so often overlooked by mainstream movie-goers in the United States, it's no wonder people look at each other and say "huh?" when the Oscars roll around. That said—do yourself a favor and go see Tsotsi, a South African film from Miramax coming out in limited release on February 24. This is undoubtedly one of the year's most powerful examples of just how valuable foreign films are to American society, telling stories we don't hear and showing lives we don't see. Tsotsi not only offers perspectives from a world away, it also brings issues to light that are relevant to human beings the world over.

The story chronicles six days in the life of Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae), a teen-aged male leader of a violent gang in the Johannesburg township of Soweto, South Africa. Tsotsi and his friends are hard edged and quick to anger, driven by their delicate balance of existence—profiting from robberies and murders while affording safety only in their anonymity amidst a dangerous and powerful ghetto.

Though the young men have formed a sort of twisted brotherhood, even that version of family is precarious. Tsotsi upsets the hierarchy after severely beating one of the group who tries to get the mysterious boy to reveal his painful past. Tsotsi goes off alone into the rainy night and ends up in an affluent neighborhood where he steals a car. Though he does not know how to drive, Tsotsi is somehow able to maneuver the car onto the road and far back into a deserted area. There, he ransacks the vehicle and discovers that he has unknowingly kidnapped a baby.

The adventure ensues as Tsotsi tries to take care of the infant, even though he knows nothing about childcare and was himself orphaned at a young age. Meanwhile, his friends and neighbors are growing suspicious as he begins to cut ties from them and won't allow anyone to enter his dingy hut. It is about this time when Tsotsi starts to panic and notices a single woman carrying a baby on her back as she goes to get her daily water. Tsotsi follows the woman, Miriam, back to her home and forces her at gunpoint to feed "his" baby. Yet, it is this relationship with Miriam that begins to whittle away the sharp edges of Tsotsi's being, revealing to him that there is hope and goodness still left in his brutal world and that all relationships need not be so forcefully primitive.

Much of this film is tough to watch—from Tsotsi's flashbacks to childhood abuse to the violent acts he and his friends commit against others, the filmmakers did not leave much to the imagination. However, one almost needs a strong distaste for Tsotsi and his gang in order to feel the film's emotional climax. Tsotsi is the unforgivable character, and he knows it; yet he still finds that there is enough morality left within him to create conflict within his conscience and even lead him to choose unselfishly, for once in his life.

Reflective of the nature and society represented in this film, there is an abundance of strong language and brutal, graphic violence, true to gang nature. Tsotsi certainly deserves its R rating, but if viewers can get past these things, particularly prevalent in the film's first half, they will be rewarded by the film's message and conclusion.

Tsotsi was nominated for both an Academy Award and a Golden Globe in the foreign language categories. It also won the People's Choice Award at the Toronto Film Festival and a 2006 Truly Moving Picture Award at the Heartland Film Festival in Indianapolis, Indiana.

MONSTERS AND CRITICS

FEB 20, 2006

By Jessica Adams, Feb 20, 2006

Framed against a tumultuous backdrop of political strife, personal grief and general un-rest, "Tsotsi" is the story of a gang leader of the same name who grew up in the slums of Johannesburg, South Africa. After losing his parents at the age of nine to the AIDS epidemic that has crippled Africa, Tsotsi takes to a life of crime and brutality. Having murdered a woman who's automobile he carjacked only to find her infant son in the back seat, "Tsotsi" follows our protagonist through the next six days as he decides to care for the child.

The film, which was nominated for Best Foreign Language film at the 2006 Academy Awards, has a rich soundtrack that carries the film and captures the urban and brash environment that Tsotsi must survive in. Mostly comprised of music by South African poet/actor/musician "Zola", the tracks are gritty and unforgiving, reflecting the urban brutality that is an everyday reality. After having grown up in the ghetto of Zola (which he later took for his stage name) in the town of Soweto, the authenticity of Zola's music is unmistakable. Having lived the streets and poor conditions himself, the soundtrack of "Tsoti" never fails in reminding the listener of the harsh way of life that most in Western society will never have to experience.

Even the tracks that are not contributed by Zola never stray in portraying their authenticity; tracks such Mafikizolo's "Mnt`Omnyama" and Unathi's "Sghubu Sam" show a gentler side of their African heritage when juxtaposed against the majority of Zola's tracks. And while not all of Zola's tracks are brash, it unquestionably draws on the complex sense of hope and redemption that is one of the film's underlying themes and questions. Can an urban thug finally face his past in order to come to terms with his future? The parallel lives between Zola and Tsotsi are unmistakable. Perhaps, unfortunately, the best comparison for Americans to reference is Eminem's poignant use of music in his semi-autobiography "8 Mile," though Eminem can't begin to compare to the gritty and weathered vocals that make "Tsotsi's" soundtrack so convincing.

LA TIMES CALENDAR LIVE FEB 24, 2006

By Carina Chocano, 24 February 2006

When the mugging he masterminds ends in murder, and a member of his gang chooses this delicate moment to make some ill-advised inquiries into his past, Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) beats his buddy senseless and runs out into the rainy night, demons nipping at his heels. He stops to catch his breath in front of a beautiful house, just as its owner is pulling up in a BMW. Tsotsi seizes the moment, and the car, shooting the woman when she tries to climb back in on the passenger side. It's not until he is nearly back to the township that Tsotsi hears the baby gurgling in the back seat.

The official South African entry for the Academy Awards and a nominee in the best foreign-language film category, "Tsotsi" was adapted by Gavin Hood, who also directed, from the novel by playwright Athol Fugard. Tsotsi — his name literally means thug in the patois of the Soweto townships — is the steely-eyed leader of a small band of heavies. There's the now out-of-commission Boston (Mothusi Magano), who once dreamed of being a teacher; Butcher (Zenzo Ngqobe) a murderous creep; and Aap (Kenneth Nkosi), a slow-witted bully with murky allegiances. Hood transposed the story from 1950s Johannesburg, where it was originally set, to the present, both for financial reasons and for greater ease of relating, though it's not exactly good news that the story adapts so seamlessly to post-apartheid South Africa. But then, that's less a comment on that country's political history than on global poverty in general, and the depressing universality of its effects. Fugard's novel ends with Tsotsi being literally crushed by the fascist state. Hood's film ends on a more hopeful note, although in the absence of a specific villain, the circumstances make you queasier. Who's to blame for Tsotsi's terrible life?

Hood avoids overt references to South Africa's political past, actually, and it's hard to know what to make of it. All of Tsotsi's victims are black, though they range from rich to middle class to poor. (The only whites in the film are a pair of more or less benign cops.) But he draws straight and steady lines from Tsotsi's criminal present to his suffering past. An AIDS orphan whose father abused him, Tsotsi eventually graduated from sleeping in the orphan hive of the stacked drainpipes outside the township to a corrugated steel shack of his own by sheer force of will and repression of memory.

The flashbacks are meant to bridge the gap between roving menace and besotted dad, but they mostly just compromise the movie's naturalism and suggest a lack of confidence in the plausibility of the premise. They also make an overenthusiastic argument for nurture in the old debate, dressing up Tsotsi's childhood traumas as latent paternal instincts, waiting for the right moment to spring: crouching nurturer, hidden father.

Whatever its weaknesses, "Tsotsi" is redeemed by its excellent performances. Chweneyagae has the amazing capacity to look like a hardened criminal one moment, a child the next. After a series of mishaps involving newspaper diapers and condensed milk, Tsotsi follows a shantytown Madonna named Miriam (Terry Pheto) home one afternoon and holds her up at gunpoint, demanding she feed his baby. Tsotsi sits and watches, his hard edges visibly softening — the implication apparently being that the key to crime reduction is to put more nursing mothers and cute babies on the street. Still, it's a pleasure to watch the interplay of emotions on Chweneyagae's face as he contemplates Miriam and imagines — you imagine — forming a little family (at gunpoint) of his own.

What makes "Tsotsi" ultimately as heartbreaking as it is, is Chweneyagae's subtle characterization. He imbues the character with a dreaminess that encourages you to dream with him, drawing you in to the overlooked tragedy of his life. By refusing to trump it all up with unnecessary bombast, distractingly famous faces, lung-collapsing histrionics and excessive post-nasal drip (as witnessed in last week's carjacked baby movie), Hood lets the story unfold at a steady, unhurried pace, cutting only when necessary, and allowing the actors, and the audience, to absorb the impact of each moment. The result is that the final scene creeps up on you quietly, with equally quiet and devastating effect. Having just this week watched some of the most idiotic screen violence I've ever seen, I can confidently attest to the devastating emotional power of nonviolence. Chweneyagae's expression at the end of the film is more jolting and painful than any bang and spurt, and Hood has the stomach not to turn away.

Roger Ebert

March 9, 2006

How strange, a movie where a bad man becomes better, instead of the other way around. "Tsotsi," a film of deep emotional power, considers a young killer whose cold eyes show no emotion, who kills unthinkingly, and who is transformed by the helplessness of a baby. He didn't mean to kidnap the baby, but now that he has it, it looks at him with trust and need, and he is powerless before eyes more demanding than his own.

The movie, which just won the Oscar for best foreign film, is set in Soweto, the township outside Johannesburg where neat little houses built by the new government are overwhelmed by square miles of shacks. There is poverty and despair here, but also hope and opportunity; from Soweto have come generations of politicians, entrepreneurs, artists, musicians, as if it were the Lower East Side of South Africa. Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) is not destined to be one of those. We don't even learn his real name until later in the film; "tsotsi" means "thug," and that's what he is.

He leads a loose-knit gang that smashes and grabs, loots and shoots, sets out each morning to steal something. On a crowded train, they stab a man,- and he dies without anyone noticing; they hold his body up with their own, take his wallet, flee when the doors open. Another day's work. But when his friend Boston (Mothusi Magano) asks Tsotsi how he really feels, whether decency comes into it, he fights with him and walks off into the night, and we sense how alone he is. Later, in a flashback, we will understand the cruelty of the home and father he fled from.

He goes from here to there. He has a strange meeting with a man in a wheelchair, and asks him why he bothers to go on living. The man tells him. Tsotsi finds himself in an upscale suburb. Such areas in Joburg are usually gated communities, each house surrounded by a security wall, every gate promising "armed response." An African professional woman gets out of her Mercedes to ring the buzzer on the gate, so her husband can let her in. Tsotsi shoots her and steals her car. Some time passes before he realizes he has a passenger: a baby boy.

Tsotsi is a killer, but he cannot kill a baby. He takes it home with him, to a room built on top of somebody else's shack. It might be wise for him to leave the baby at a church or an orphanage, but that doesn't occur to him. He has the baby, so the baby is his. We can guess that he will not abandon the boy because he has been abandoned himself, and projects upon the infant all of his own self-pity.

We realize the violence in the film has slowed. Tsotsi himself is slow to realize he has a new agenda. He uses newspapers as diapers, feeds the baby condensed milk, carries it around with him in a shopping bag. Finally, in desperation, at gunpoint, he forces a nursing mother (Terry Pheto) to feed the child. She lives in a nearby shack, a clean and cheerful one. As he watches her do what he demands, something shifts inside of him, and all of his hurt and grief are awakened.

Tsotsi doesn't become a nice man. He simply stops being active as an evil one, and finds his time occupied with the child. Babies are single-minded. They want to be fed, they want to be changed, they want to be held, they want to be made much of, and they think it is their birthright. Who is Tsotsi to argue?

What a simple and yet profound story this is. It does not sentimentalize poverty or make Tsotsi more colorful or sympathetic than he should be; if he deserves praise, it is not for becoming a good man but for allowing himself to be distracted from the job of being a bad man. The nursing mother, named Miriam, is played by Terry Pheto as a quiet counterpoint to his rage. She lives in Soweto and has seen his kind before. She senses something in him, some pool of feeling he must ignore if he is to remain Tsotsi. She makes reasonable decisions. She acts not as a heroine but as a realist who wants to nudge Tsotsi in a direction that will protect her own family and this helpless baby, and then perhaps even Tsotsi himself. These two performances, by Chweneyagae and Pheto, are surrounded by temptations to overact or cave in to sentimentality; they step safely past them and play the characters as they might actually live their lives.

How the story develops is for you to discover. I was surprised to find that it leads toward hope instead of despair; why does fiction so often assume defeat is our destiny? The film avoids obligatory violence and actually deals with the characters as people. The story is based on a novel by the South African writer Athol Fugard, directed and written by Gavin Hood.

This is the second year in a row (after "Yesterday") that a South African film has been nominated for the foreign film Oscar. There are stories in the beloved country that have cried for a century to be told.

THE INDEPENDENT MAR 19, 2006

By Jonathan Romney, 19 March 2006

Gavin Hood's South African drama Tsotsi won this year's Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film - but we shouldn't hold that against it.

This category of the Oscars tends to favour uplifting human interest stories, and Tsotsi undeniably ticks certain boxes that generally win Academy voters' approval: notably, those marked "redemption" and "universality". Universal Tsotsi certainly is: it belongs to a familiar tradition of films about damaged disadvantaged youth, taking its place alongside the Brazilian City of God and Pixote, Buñuel's Mexican drama Los Olvidados, early-1990s African-American dramas such as Boyz n the Hood or Juice, or even recent UK contender Bullet Boy

.

But even if Tsotsi isn't wholly distinctive, it's accomplished and gripping - and despite the above similarities, is very specific to its setting. Its anti-hero (non-professional newcomer Presley Chweneyagae) is a 19-year-old criminal in a shanty town near Johannesburg; his name means "hood" or "thug", causing one of his sidekicks to object, "Tsotsi? That's not a real name." In fact, Tsotsi does have a more prosaic name; why he prefers not to use it, and how he comes to reclaim it, is part of the story.

From the start, Tsotsi is unmistakably a hard case. At a busy station, he scans the crowd with an icily efficient gaze, seeking out a likely victim. He chooses a dapper elderly black man, and in a nightmarishly terse sequence - the film is good at evoking peril in cold, spare blasts - Tsotsi and his three accomplices surround the man, rob him and stab him.

Tsotsi hardly seems a likely candidate for redemption, especially when we see him administer a brutal beating to sidekick Boston (Mothusi Magano), who's reckless enough to challenge him on the topic of "decency". But then, after shooting a woman and stealing her car, Tsotsi finds himself with a baby on his hands (or rather, in a paper carrier bag).

This is where you have to decide whether or not you're going to place your faith in Tsotsi as a narrative. It's not that much of a problem, surely, to credit that even a merciless desperado would balk at harming or abandoning a baby; it's even plausible that he should try ineptly to tend to it. The problem is simply that Hood's script too transparently primes Tsotsi for a moment of truth. Distraught after beating Boston, Tsotsi runs off across a wasteland in pouring rain - and the film flashes back to him as a young boy, dashing in terror across the same plain, years earlier.

When Tsotsi coerces young mother Miriam (Terry Pheto), a neighbour of his, into helping with the baby, we see his cold features begin to soften with need, tenderness and a sort of muted awe, and we get further flashbacks to his own mother - seen, in child's-height point-of-view, dying of Aids - and brutal father. The awkward crowning touch is that Tsotsi announces that he'd like to call the baby David - his own real name. Here the film becomes considerably less hard-nosed, and threatens to become just another Oscar-friendly drama about finding the inner child.

To Hood's credit, the film never uses the baby to try to melt our hearts, or Tsotsi's. There's nothing remotely charming or humorous about Tsotsi's attempt to care for the hapless bundle. Our initial anxiety about his tender mercies turns to horror, when he leaves the child sucking at a tin of condensed milk, then returns to find ants swarming all over him (Tsotsi would fit wonderfully with last week's Belgian drama The Child in a bad babycare double bill).

The film's biggest problem - I have no idea whether this is inherited from the Athol Fugard novel on which it's based - is that it's structured too neatly, with redemption coming for Tsotsi just when he needs it most. Its 91-minute running time is perhaps a little too spare: at the start, the film doesn't give us enough of the hard, unforgiving petty hood to allow this part of his character to breathe, making his later thawing seem abrupt and contrived. It's a shame, because in the opening sequences, Chweneyagae's baleful detachment makes Tsotsi's angry emotional repression genuinely troubling.

But rather than see it as realism that fails because of overstatement, Tsotsi makes most sense if you take it as melodrama in a vividly realistic setting. Its atmospherics are laid on with almost Gothic intensity; Lance Gewer's widescreen photography establishing a toxic-looking shanty town setting, a sickly yellow-pink haze lacing the smoking chimneys and barbed wire. There's a nightmarish desolation in the tautly uncomfortable scene of Tsotsi's stalking of a beggar in a deserted underpass. And there's some effective editing: a shot of the young David huddled at night in a concrete pipe cuts to a whole stack of pipes, each with its own permanent child occupants.

The overall edge is rather blunted by a soundtrack that feels that bit too obviously packaged (lots of kwaito, a punchy contemporary township style with touches of hip-hop); and the score could have done without its touches of angelic gospel. Tsotsi is softer than it might have been, but even so, it's extremely watchable, as well as offering a rare cinematic insight into South African life after apartheid (there's only one white character, a minor player). And unlike, say, City of God with its favela gangster flash, Tsotsi couldn't be in any way accused of glamourising its setting. It's an effective, sincere film, made with - although you wish the script hadn't stressed the word quite so much - decency.

THE SUNDAY TIMES MAR 19, 2006

Cosmo Landesman, 19 March 2006

Tsotsi is a refreshing tale set in South Africa that makes no attempt to glamorise brutality

In theory, I should have hated Tsotsi. Set in a shantytown on the outskirts of contemporary Johannesburg, it's about a violent 19-year-old thug called Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae), who undergoes a change of heart after stealing a baby and gives up his criminal way of life. Ah, isn't that sweet? What's more, the film puts forward the dubious idea that because Tsotsi grew up in poverty, he turned to criminality. But I have to admit that this is a great, riveting work of drama.

It's a gangster film in the tradition of City of God, but there's no handheld camera wobbling all over the place. It's full of loud, Third World vibrancy, but has moments of quiet and stillness, and allows us to slip into the lives of its characters. We first meet Tsotsi as he strolls through the shantytown streets, giving the finger to anyone who disses him. Later, we watch as Tsotsi and two members of his crew target an old black man to rob. They take his money, then, for no reason, take his life.

More brutality follows. The boys are having a drink when Tsotsi is questioned by one of his gang about his past, and whether he is a man with "any sense of decency". He goes berserk and beats him up. Tsotsi then goes off, hijacks a car, shoots the woman driver, drives off and discovers a baby in the back.

Suddenly, Tsotsi is a daddy - one who doesn't have the faintest idea how to look after the child. In one memorable scene, he returns home to his filthy shack and finds the baby covered in ants. He then forces a local single mum, Miriam (Terry Pheto), at the point of a gun, to breast-feed the baby. Seeing her loving care makes him look at himself again.

What's so refreshing about this film is that there's no attempt to glamorise Tsotsi, his crimes or his lifestyle. There are no cool gangster moments. Rarely has the brutality of the thug been so powerfully presented. This is not an aren't-things-awful film, nor one that goes for an easy feelgood effect.

It's a tribute to the director and writer Gavin Hood's skills as a storyteller that he portrays Tsotsi's victims in such a way that we really care what happens to them. We see the fear, bewilderment and humiliation of a wheelchair-bound beggar as Tsotsi torments him - a harrowing scene you won't forget.

The story line of Tsotsi's change of heart may be a little flimsy, as he gets in touch with feelings he has long suppressed. The idea is that what reforms him is his contact with humanity. But such is the performance of Chweneyagae - his ability to move from vicious killer to weeping child - that it all seems totally convincing. Four stars

THE OBSERVER MAR 19, 2006

By Philip French, Sunday March 19, 2006

Stark life-or-death choices are convincingly real in Tsotsi, Gavin Hood's tough, Oscar-winning drama, says Philip French

Since the introduction of apartheid in the late 1940s, most people of goodwill in Britain have recognised it as something morally abhorrent. A long time passed, however, before any concerted action was taken. Meanwhile white South African teams played rugby and cricket against this country and movies were made there with British stars attending premieres in Johannesburg from which black actors were excluded. British emigrants and visitors to South Africa constantly regaled us with that complacent old cliché about having to go there to understand or judge the situation. This was not true of course. To understand how unjust, demeaning and dehumanising apartheid was, all we needed to do was to read and listen to courageous witnesses like Father Trevor Huddleston, Alan Paton, Nadine Gordimer and Albie Sachs.

One of the most notable of the South African writers who made apartheid vivid in our minds is Athol Fugard, and many of us regard his plays Blood Knot, Sizwe Bansi Is Dead and The Island as among the most powerful theatrical experiences of our time. In the 1960s he wrote a novel, his only one, about a black criminal in the South Africa of the 1950s. It wasn't published until 1980 and now, updated to the present, it's been filmed as Tsotsi, written and directed by Gavin Hood, a white South African who studied cinema in California. The setting is post-apartheid, but crime is more widespread than ever as is unemployment, and little has changed in the shantytowns. But a wealthy black man can now harass a white policeman and a new threat hangs over the nation with hoardings everywhere proclaiming: 'We are all affected by HIV/Aids'.

This modestly budgeted social thriller won an Oscar as Best Foreign Language Film, the foreign language being Tsotsi-Ttaal or Isicamtho, a patois spoken in African townships, that draws on Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana and Sotho. 'Tsotsi' is also a slang term for a young black criminal, and the movie focuses on one such living in a wretched township on the outskirts of Johannesburg. He's in his teens, illiterate and innumerate, and has taken the name Tsotsi as a nom de guerre to keep the horrors of his past at a distance.

Tsotsi has a certain surly charm, enough to command the allegiance of a small gang, and we're introduced to him on a particularly dreadful day. In a sequence that recalls a famous robbery sequence in Bresson's Pickpocket, Tsotsi and his cohorts target a middle-aged man with a wallet full of money at a railway terminal. They follow him on to a train and in the course of the theft the victim is killed with an ice pick.

Later that night a drunken member of the gang taunts Tsotsi for his inability to show remorse, telling him he doesn't understand the meaning of decency. Tsotsi gives him a near fatal beating, and then takes off on a walk through the wilderness that leads to an affluent neighbourhood, where on the spur of the moment he steals a car, shoots its female owner and drives away. On the back seat is a small baby. When he ditches the car he takes this little boy with him. Is he going to abandon or kill the child to cover his tracks? This moment is almost unbearably tense.

Ever since Chaplin's The Kid, when a man is left to care for a child in a movie, it's usually an occasion for comedy or redemption and sometimes both. Tsotsi reluctantly and very gradually starts to care for the child and there's nothing funny about his progress - especially when the condensed milk he feeds the boy attracts an army of ants.

Redemption and retribution are delayed. At the point of a gun Tsotsi compels a widow, herself raising a child in the shantytown, to breast-feed the baby, and she, beautifully played by Terry Pheto, points the way to common decency. He leads a raid on the baby's grand home, where we see the privileged life a few successful middle-class black people have created for themselves in the new country, and he acts to prevent another murder.

A riveting encounter with an elderly beggar in a wheelchair, crippled in an underground mining accident, leads to Tsotsi asking, 'Why do you go on?' In a series of brief flashbacks, we learn that Tsotsi ran away from home as a child, escaping from a brutal father, leaving behind a beloved mother dying of Aids.

This deceptively simple movie brings to mind Italian neo-realist classics of the 1940s, and Presley Chweneyagae, an amateur actor, is wholly convincing as the disoriented Tsotsi. The movie begins by presenting him in the most unsympathetic of lights and we are gradually led to understand what has shaped him and how he might change. It flirts with sentimentality in the late stages but ends on a note of hard-won affirmation.

THE TELEGRAPH

MAR 19, 2006

by Zadie Smith, 2006

The premise of Tsotsi (15) has a biblical clarity. A young thug from a South African township shoots a middle-class black woman in the stomach and drives off in her car. A mile down the road he hears a baby crying in the back seat. The audience gasps in that odd mixture of surprise and recognition that great story-telling affords.

Everything flows from this point with the inevitability and moral didacticism of the Moses story. But the setting is fascinating, everything is news: the township shacks, the glamorous black middle class, the tube station, the concrete rings in which orphaned children sleep out in the open air.

At the centre is Tsotsi himself (Presley Chweneyagae), who needs no mask to commit his acts of terror - his face is a mask.

In a scene so menacing it outpaces the deadliest moments of Scarface itself (an obvious model), he stalks a crippled man through a train station, a beast on the hunt. Frantic local hip-hop, 'kwaito', choreographs his frenetic impulse to violence; gospel swells as we glimpse the possibility of redemption in a boy who seemed lost to all pity. I wept throughout the last 15 minutes.

Unfortunately, unlike the woeful 50 Cent movie, this film - from which young black men could genuinely profit - will be seen by Ekow Eshun and nobody else. It will not sell for five quid on the Kilburn High Road and no one will pass it round a playground.

LOOKING CLOSER JOURNAL

JAN 18, 2007

Question: What happens when a newborn baby ends up in the care of a lawless, gun-toting gangster?

Answer: That really depends on the gangster.

If Gavin Hood's directorial debut, Tsotsi, is going to make a lasting impact, it will have to succeed on word-of-mouth reviews. It just doesn't have the stuff that makes a flashy marketing campaign. Let's skip the fact that most people will have trouble pronouncing the title... Tsotsi is a tough, violent film about trash-talking thugs and hoodums in Johannesburg. And thus it's probably not the kind of movie you'd go see expecting to be inspired. It includes no recognizable movie stars. And most American moviegoers will probably pass by a film set in a South African slum, especially if they have to read subtitles. (The characters speak Tsotsitaal.)

Take note: It's time to turn over a new leaf. Tsotsi is one of the must-see movies of 2006. You'll need a strong stomach, as the crooks who think they rule these shantytown streets are reckless, foul-mouthed, and willing to shed blood in order to get what they want. But don't miss it. It's the starkness of that darkness that makes Hood's big screen adaptation of Athol Fugard's novel such a satisfying story of redemption, the kind of thing to stir compassion in viewers' hearts, and to remind us that sometimes God can reach even the most prodigal of his children.

Hood's film follows a young gang leader through six days of crime, fear, and moral struggle. After he steals a woman's car without thinking to check the backseat, Tsotsi (the name means "gangster") discovers he has absconded with far more than he'd planned, namely, the woman's infant son. Having never cared for a child before, Tsotsi debates whether to dump the child or to return him to his parents. But the cops are on his trail, combing the vast, chaotic Johannesburg townships for clues, and he's forced to hide the baby in his apartment, keeping the screaming, hungry, frightened child concealed from his partners in crime.

Make no mistake this isn't another caper about childcare along the lines of Raising Arizona or Three Men and a Baby. This is a hard-hitting story about the tug-of-war between one young man's sinful nature and the still, small voice of conscience that still whispers in his ear.

Some may view its tale of how a baby can melt a murderous heart to be sentimental or formulaic and they're right. But Hood gives the simple storyline a compelling urgency, as though it is a lament not just for this character but for the countless "feral" youth of South Africa, and for the families devastated by AIDS. His film has surprisingly jagged edges that get their hooks into you and pull you in, and he convinces you with a level of detail that speaks of first-hand experience with the people, their environment, and the economic crisis that divides them.

The whole endeavor is fueled by adrenalin-rush music, a blend of contemporary African styles called 'Kwaito,' which draws you along the troubling start to the riveting finale.

Fugard's original novel was based in 1950's South Africa, but Hood has done a fine job of updating the material, preserving its themes of conscience and redemption, while presenting audiences with an unnerving portrait of present-day Johannesburg, a sight that should spur viewers to deeper concern and braver action in serving a part of the world where God's children are in desperate need.

Actor Presley Chweneyagae is well-cast, playing the strong, silent type of crook. He says very little, but he gives a complex and compelling performance, representing a generation driven by a need to survive, and lacking guidance and love.